Stomping through the bush I experienced the faintest of, all that I can describe as, chemical zaps and knew that I’d picked up another very unwelcome hitchhiker. Resisting the urge to scratch the affected area I ducked behind a convenient tree and inspected the site in question. Sure enough, in the centre of a red circular spot was the back end of a tick that was now upended, firmly attached and happily feeding on my blood. For any of us who spend time in the bush this is an all too familiar scenario as ticks are unfortunately a fact of life for those who enjoy or work in the outdoors. That said, how many of us have stopped to think about the pesky creature in question?

At the class level ticks are members of the eight-legged Arachnida along with their well-known spider and scorpion relatives and have been around for at least 300-400 million years. They are all parasitic blood suckers that undergo several moults, usually interspersed with blood feeds, before the final moult into a reproductive adult. At the family level, ticks are classified as either hard ticks (Ixodidae), which have a hardened scutum (middle part of the thorax) or soft ticks (Argasidae), which lack this feature. Female Ixodidae ticks lay a single large batch of eggs before dying, whilst female Argasidae lay several smaller batches of eggs.

Most ticks have three discrete hosts as part of their lifecycle. These hosts do not need to be the same species. This three-host lifecycle sees a hatched larva attach to a host, feed, then drop off. It then moults to become a nymph which again requires a host to feed on before dropping off. The nymph then again moults and emerges as an adult that again requires a new host on which to feed and mate. The blood engorged fertilised females drop off the final host and lay their eggs before dying.

In contrast, the introduced Australian Cattle Tick (Rhipicephalus australis) is a one-host tick and from the time it hatches from its egg and is picked up by a host, usually a passing cow, it will go through the life stages of larva, nymph and then adult on the one host animal.

Most ticks spend most of their life waiting for a new host and there is high mortality due to predation and starvation during this ‘waiting’ time. Being obligate parasites, it is vital that ticks are able to efficiently find a host. To this end ticks (and mites) possess a unique sensory organ on their front legs called Haller’s organ. This specialised organ is sensitive to heat, carbon dioxide and other chemosensory cues given off by a potential host. To facilitate host attachment, ticks crawl onto the end of low growing vegetation then extend and wave around their receptor equipped front legs and wait to ambush a host. This waiting ‘ambush’ behaviour in ticks is called ‘questing’. As an animal brushes past, the alerted tick grabs onto the host and then crawls over the animal before finding a suitable area to attach and feed.

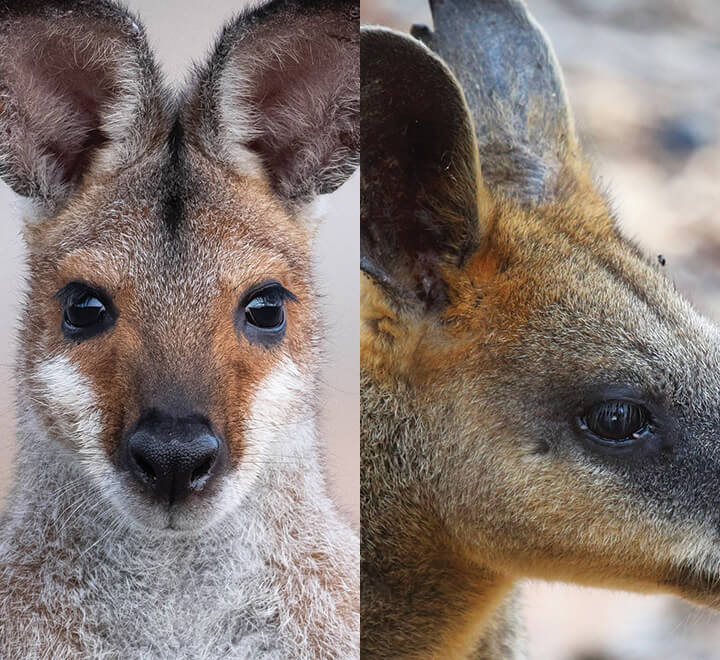

In Australia there are about 74 tick species with names such as Robert’s Bird Tick (Argas robertsi), Ornate Kangaroo Tick (Amblyomma triguttatum), Southern Reptile Tick (Bothriocroton hydrosauri) and Wallaby Tick (Haemaphysalis bancrofti). The common name gives an indication of their preferred host type. Of these 74 only a couple are known to make a meal of us.

In South East Queensland the most commonly encountered tick is the three-host Paralysis Tick (Ixodes holocyclus). This one tick is responsible for 95% of human tick bites in eastern Australia, the occasional hospital visit (I’ve been there), and several fatalities. It’s also known for innumerable expensive vet visits, sick livestock and for the death of many animals, as a single feeding female can be deadly if not removed in time. Given their long association and exposure to this tick, native Australian wildlife have a much higher tolerance level.

Although it’s the same beast, the Paralysis Tick is also referred to as grass tick, seed tick and bush tick depending on the lifecycle stage of the animal. If you are unlucky, you can pick up multiple pin hole sized larval ticks if you brush past a hatched egg mass which can result in intense irritation which people call ‘scrub itch’. However, this term should rightly be reserved for infestations of larval mites. The tick-transmitted disease, Queensland Tick Typhus, is also colloquially called scrub typhus, but in the medical literature Scrub Typhus is reserved for a mite-transmitted infection.

he Paralysis Tick occurs along the eastern seaboard from Cape York all the way through to Lakes Entrance in Victoria. It is found in damp, humid, bushy areas as these environmental conditions reduce the risk of the tick drying out and dying due to desiccation. When it comes to host selection, the Paralysis Tick is not particularly choosy and has been recorded parasitising 34 mammal, 7 bird and numerous reptile species. In SEQ, scientific studies indicate that bandicoots are both a major and vital host, and a stable number of bandicoots are required to sustain a Paralysis Tick population.

A typical lifecycle of a Paralysis Tick is around one year, from laid egg to adulthood. This is influenced by temperature, humidity and the time required to find hosts. Considering that a tick only spends about 20 days of its life feeding, this leaves a lot of time for hiding in the leaf litter and questing. Under experimental conditions unfed larvae can survive up to 162 days, unfed nymphs for 275 days and unfed females up to 77 days.

Although there is a distinct ‘tick season’ (October to December), when females are most likely to be encountered, in theory, ticks can be picked up at any time of the year at any stage of their lifecycle. That said, the six-legged pin hole sized larvae are most likely to be found late February to May, the eight-legged pinhead sized nymphs April to September and the unfed 4mm long female, which will expand to about the size of a grape once replete, October to December. Males are also active in this period but are unlikely to be noticed as they very rarely feed on a host. They are little vampires, and their mouthparts are adapted for feeding on blood-engorged females, on which they leave distinct feeding scars.

The female Paralysis Tick has long mouth parts, the ends of which are equipped with cutting edges that are used to slice into the host’s skin. The mouth parts also have tiny backward facing barbs, which are also inserted into the wound. The tick then stabilises itself in its inverted feeding position by splaying out its palps.

Feeding is facilitated by the production of numerous biologically active molecules that are pumped into the wound through the tick’s saliva. In combination, these molecules overcome the host’s immune response and allow the tick to feed for days. These molecules include anti-coagulants, anti-platelet, vasodilators (chemicals that open blood vessels to encourage blood flow) and anti-inflammatories to name a few. The Paralysis Tick also produces a neurotoxin that can induce motor paralysis. In an actively feeding female, neurotoxin production peaks around days 4-5, then tapers off.

So next time you are ‘attacked’ by a tick, while you are cursing the inevitable itchiness or worrying about allergies and possible diseases, try to also be amazed by this efficient piece of natural engineering. Rejoice in the knowledge that you have got a good bandicoot population and, by association, other native animals to act as hosts to keep the tick population ‘ticking’ over.

First Aid and Tick Removal

A Google search for tick first aid/removal will bring up contradictory information even from respectable sources. It is an evolving science with medical literature and research being updated regularly. All reputable information however agrees that tick removal/death should be carried out as soon as practical once the tick is detected. Removal techniques should avoid aggravating the tick or squeezing the tick’s body, to minimise the risk of the tick injecting more of its saliva (and chemicals) into the wound.

The Australian Department of Health currently recommends the removal of adult ticks using fine tipped forceps (not household tweezers), by grasping the tick as close to the skin’s surface as possible. Pull upwards with steady pressure and avoid jerking or twisting the tick.

The Australasian Society of Clinical Immunology and Allergy recommends killing an adult tick in place by using an ether-containing spray and then either gently brushing the dead tick off or allowing it to fall off by itself. Larval and nymph ticks should be killed by applying a permethrin-based cream (such as Lyclear), which is designed for killing mites (e.g. scabies).

Seek medical attention as soon as possible if you have an allergic response to a tick bite.

Tony Mlynarik

Land for Wildlife Officer

Brisbane City Council

There is a common tale that Casuarina and Allocasuarina are tick trees, that ticks live and thrive on them. This is appears to be quite untrue. However, it is commonly used to frighten people into clearing these trees on their land. Unfortunately, the casuarinas are critically important food trees for the threatened Glossy Black Cockatoo. Do you you know the origin of this myth and how it can be combatted?

Maybe because bandicoots hang out with she-oaks? They are hosts for paralysis ticks and forage on Casuarina root nodules.

I can attest to casuarina being commonly associated with ticks. My kids have a tree house in one of nearly 100 that we have. They spent a whole day doing nothing but treehouse adventures and by the end of the day there were 70+ ticks that needed removing (they were all tiny, so I feel it may have been a recent hatch)

Since then we are wary around the casuarinas and make sure that we wear repellent when working or playing amongst them.

Paperback also seem to be a fairly popular host for them as well…

Any information or thoughts re ticks on Echidnas- I understand-links have been raised re humans potentially acquiring mammalian allergies if ‘ bitten’ by ticks found in tick & bandicoot areas. However curious re

A: Echidnas needing tick removal ?

B:: Thoughts re allergy variants potentially from monetremes ?