(Above:) This patch of native vegetation is fenced off to encourage a dense understorey for

invertebrates and other wildlife that are dependent on them.

Have you ever wondered why distinctive and unique plants occur in different areas and why they have certain relationships with fauna? Well it has a lot to do with soils and their geology, location, landform and aspect. Soils can also help determine the appropriate strategy for land management, ecological recovery and choosing plants for revegetation.

Our 5 acre property with two dams is on the road to recovery, utilising remnant vegetation, natural regeneration and planting, with an emphasis on clump and thicket establishment for fauna habitat and shelter. This includes small birds, invertebrates, reptiles, frogs and especially Red-necked Wallabies as they need resting places in hot summers, breeding places and safe locations to raise their young and to feed.

Our property lies within a bioregional ecological corridor that has unique and diverse ecosystems including Chambers Creek, Norris Creek, the Logan River, Jerry’s Downfall, Flesser Reserve and wetlands that are mostly on private property. The elevated ridges have sandstone-derived deep sandy soils with a freshwater lens within an impervious basin, which supplies bores and wells all year. There are many aquifers, springs and a wetland heath – a valuable ecological commodity to all fauna, including us.

A family of Tawny Frogmouths in a Grey Ironbark (Eucalyptus siderophloia).

Buff-banded Rails are taking advantage of the restored habitat.

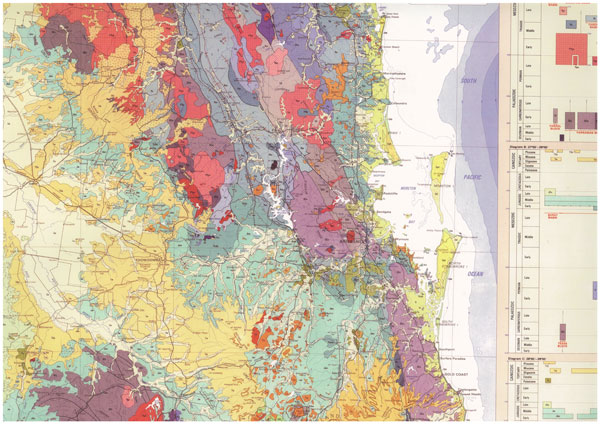

(Left:) The native passionfruit vine (Passiflora aurantia var aurantia) is a gentle climbing vine with red stems, flowers and fruit. In contrast, the aggressive introduced Corky Passion Vine has black fruit. (Above:) Part of the Moreton Geological Map.

The wetlands provide essential habitat and shelter for threatened frogs, invertebrates, reptiles, bandicoots, small mammals and birds. The wetlands are adjacent to forest of Scribbly Gum, Pink Bloodwood and Rusty Gum, with geebung, banksia, heath, herbs and native grasses. These forests provide critical habitat for koalas, (possibly) quoll and macropods (wallabies and kangaroos). Macropods require large areas of contiguous forest to allow them to move safely from the grazing meadows on alluvial floodplains of the Logan River to forests on higher ground where they shelter and breed. Unfortunately, a multi- lane motorway and underground pipeline has been approved and will bisect these unique ecosystems, causing isolation, fragmentation of essential habitat and will threaten their long-term survival.

The floodplain soils have deep, dark brown-black, loamy-clay soils that are fertile, nutrient rich, moisture holding and drought tolerant. They are dominated by Queensland Blue Gum, also called Forest Red Gum (Eucalyptus tereticornis), and form part of an endangered ecosystem (ie. less than 10% remains) due to past clearing, grazing and agriculture.

Queensland Blue Gum is a preferred food tree for koalas. Other dominant trees are Grey Ironbark (Eucalyptus siderophloia), Gum-topped Box (Eucalyptus moluccana) with Carbeen or Moreton Bay Ash (Corymbia tessellaris), Soap Tree (Alphitonia excelsa) and several wattles. These fertile soils support diverse invertebrates which are e cient soil conditioners – earthworms, ants, crickets, beetles, cicadas, spiders and centipedes. Similar soils on our property have deep cracks during dry times and close following wet seasons. They drain slowly and develop ephemeral ponds with sedges, lilies and rushes that enable opportunistic frog breeding.

Floodplain areas sometimes form galgais, also called melon holes, which are small, ephemeral, shallow lakes that provide favourable habitat for Swamp Tea-tree (Melaleuca irbyana), a tree that is only found in South-east Queensland, and forms part of a listed endangered ecosystem.

Despite minor grazing, we have a diverse understorey including scented-top grass, love grass, kangaroo grass, barb-wire grass, sedges, club-rush, jasmine, glycine, spade ower, amulla, blue trumpet, native cobbler’s pegs, blueberry lilies and red-flowering native passion vine. There are also a range of regenerating rainforest plants due to the proximity of the Logan River including Rough-leaved Elm (Aphananthe philippinensis), Whalebone Tree (Streblus brunonianus), Tuckeroo (Cupaniopsis anacardioides), White Cedar (Melia azedarach) and laurels.

The soils up on the small sandstone ridge changes to red-brown sandy loam with areas of fine white powdery subsoil embedded with large red iron rocks. The vegetation also changes to Rusty Gum (Angophora leiocarpa), Pink Bloodwood (Corymbia intermedia), Casuarina and Dogwood (Jacksonia scoparia).

The diversity and amount of fauna has increased with the recovery of the understorey as there is now a greater range of available food resources. The understorey attracts a multitude of invertebrates such as numerous species of ants and spiders. The invertebrates attract a diverse range of birds including the pacific baza, dollarbirds, wrens, thornbills and honeyeaters. There are also pigeons, doves, koalas (not for the last two years) and Red-necked Wallabies. Other interesting species include gliders, microbats, fruit bats, small-eyed snakes, eastern brown snakes, keelbacks, blue-tongue skinks, a buff-banded rail that was befriended by a guinea fowl, whipbird, grey-crowned babbler, brown falcon, broad-palmed rocket frog, dwarf tree frog, graceful frog and ornate burrowing frog.

Once the relationship between soils, geology and vegetation has been determined, there needs to be a sharper focus upon the types of weeds and their impact on native species, ecosystem health and function. Weeds are often indicators of past practices including soil loss from clearing, cultivation, overgrazing, roads and edge effects, and stormwater into creeks carrying sediment and higher nutrients, resulting in rapid colonisation of stream banks. Generally, areas with lower nutrients on sandstone or dry slopes, metamorphic or heath have less impacts from weed than fertile, higher nutrient areas with stock, creeks, wetlands and gullies.

It is better to treat weeds as an ally rather than the enemy. After all they are non-native plants and may dominate an area, but they can also prevent soil erosion, provide mulch, habitat, food resources and shelter. By observing fauna interaction during flowering and fruiting you can determine how the weeds are being spread. For example, possums, birds, bats and rats disperse the seeds of pepper trees, camphor laurels, pine trees, privet, duranta, lantana, ochna, corky passion vine, deadly nightshade and climbing asparagus. Other modes of transport are wind, water and mobile animals such as stock and macropods. Machines can spread cobbler’s peg, khaki burr, annuals, pine trees, tipuana and grasses. Note that the seeds of cobbler’s peg can remain viable for 20+ years! Some weeds really are worse than others!

A major contributor to ecosystem decline is from introduced grasses such as guinea grass, signal grass, molasses grass and swamp foxtail, all of which have a short lifecycle, are tall and bulky, and dry out in winter and spring, increasing re intensity and frequency. These introduced grasses provide a clear example of how disastrous environmental weeds can be. The consequences from these introduced grasses can be deadly for native flora and fauna, especially re-sensitive legumes, herbs, ferns, shrubs and especially for many invertebrates that shelter in gullies during winter dormancy and are killed by hot, frequent fires.

It is vital to adopt the precautionary principle regarding re use, and to manage mosaic patches to allow regeneration for several years without re. I recommend the book The Biggest Estate on Earth: How Aborigines Made Australia by Bill Gammage.

Knowing your weeds and being forewarned will help break the perpetuating weed cycle. It is important to adopt the precautionary principle with weed management and avoid wholesale clearing or control measures that will remove all food resources, shelter, shade and result in another set of weeds that could be worse than the last ones. It is important to remove patches of weeds and then replace them with diverse native flora and food resources as quickly as possible.

My theory on weed control can be summarised as Reduction, Prevention and Intervention:

- Reduction in size, extent and population. Reduce weed trees and vines to a manageable shrub. Depending upon extent of problem, choose manual removal, pruning, stem injection or cut and swab with glyphosate to trees and shrubs, and mosaic spraying for invasive groundcovers and grasses.

- Prevention of seeds and mature fruit, and prevention of weeds spreading to new areas especially annuals and grasses through slashing or mowing.

- Intervention of the plant life-cycle by allowing owers for diverse invertebrates to forage but intervention to stop fruit and seed maturity.

Whilst you can be responsible and maintain a healthy habitat on your own patch of land, ultimate success is also dependent on cooperative management by adjoining landholders to recognize weeds and prevent them from getting out of control, and to retain habitat and vegetation linkages that enable fauna movement.

Article and photos by David Gasteen, Land for Wildlife member, Munruben, Logan

I am currently studying Restoration Ecology at CSU as part of a Sustainable Agriculture degree. I am required to investigate and review a restoration project for my assessment. Being a local (Logan Village) and a fellow Land for Wildlife property owner I am very interested in learning more about this project for my study. I am hoping to get in touch with David. Can my comments and contact details please be passed on requesting he get in touch with me. Thanks. Peta.

Hi Peta. I have passed on your details to the Logan City Council Land for Wildlife team and they will get in touch with David and pass on your request. All the best.