To tell the story about Queensland’s rarest bird, I am going to start with a tale about the Californian Condor. his huge, long-lived bird of prey was once widespread across North America, but numbers plummeted, and by 1987 there were only 27 birds alive, all in captivity. Through significant investment, the Californian Condor’s population increased to 435 birds in 2015. Now hundreds of these magnificent birds are flying free in the wild.

Although not quite as remarkable in stature, the Eastern Bristlebird is arguably Queensland’s condor. Historically, the Eastern Bristlebird (northern population) extended from about Glen Innes in NSW north to the Conondales. Surveys in 1988 counted about 154 wild birds; 30 years later, numbers were down to less than 40. The current estimated wild population of Eastern Bristlebirds is about 38 individuals – six in Queensland and 32 in northern NSW.

All recent records from Queensland are from one Land for Wildlife property near Lamington Range in the Scenic Rim. Researchers are working in partnership with the landholders to actively manage and protect this population. Understandably, the Eastern Bristlebird is listed as Endangered under national and state legislation.

In 2013, a difficult decision was made by researchers to capture wild Eastern Bristlebirds from an at-risk population in northern NSW. These individuals were added to existing captive birds at Currumbin Wildlife Sanctuary to expand the captive breeding program. Since 2015, the captive population has successfully bred and hopefully this year a new facility in SEQ will open to further expand the captive breeding program.

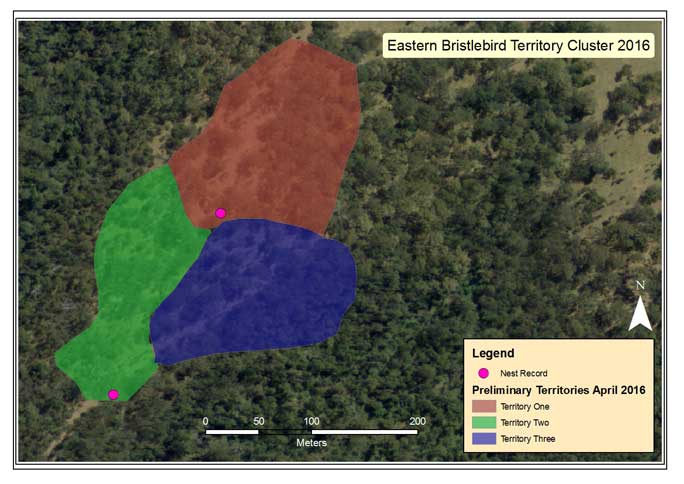

Ecologist, David Charley has been monitoring Eastern Bristlebirds in SEQ and northern NSW since 1998. He has found that their populations are now quite stable, despite being so low. Male bristlebirds establish a territory about 1.5 hectares in size and will regularly patrol their territory ensuring that neighbouring Eastern Bristlebirds do not encroach. David has seen male bristlebirds ‘yelling’ at each other over their boundary ‘fences’. All known Eastern Bristlebird territories are in steep and rugged terrain.

In 2016, David confirmed three territories in Queensland, each with a pair of birds, all on one Land for Wildlife property. See map below.

David’s survey work includes finding nests and eggs, locating new birds, determining territories and managing their habitat. The Eastern Bristlebird is a ground-dwelling bird that builds a nest close to the ground, usually in dense tussock grass, such as Poa species. Their nests always occur on ground underneath gaps in the canopy, never under the canopy itself. This may be because individual tussock grass clumps grow larger and more dense in full sunlight rather than under a tree. They also seem to nest near old nests, but never re-use an old nest. Eastern Bristlebirds keep their nests very clean – there are no droppings or feathers. Assumingly, this is a strategy designed to avoid detection by predators.

A unique survey technique used by researchers is the conservation dog, Penny, who has been specifically trained to detect Eastern Bristlebirds including their nests, feathers and droppings. She can easily move through potential habitat using her excellent sense of smell to detect bristlebird traces.

Penny is only used once per breeding season per site, with subsequent surveys done on foot by researchers. Playback of the bristlebird call is only used rarely in remote locations inaccessible to Penny, where human visitation is low and outside of the breeding season. The indiscriminate, regular use of call playback is highly disturbing to bristlebirds, as the resident male spends his time looking for the socalled intruder rather than caring for the female and young.

A crucial piece of the Eastern Bristlebird puzzle is its dependence on appropriately fire-managed landscapes. If there is not enough fire, its habitat becomes overrun with shrubs and herbs (e.g. Lantana, Crofton Weed, wattles and Red Ash, Alphitonia excelsa), which shade out and prevent germination of essential tussock grasses. If fires are too hot or too extensive, the birds cannot find escape routes or refugia and will perish in the fire. Eastern Bristlebirds are poor fliers and cannot fly far to escape fires. Appropriate fire management is therefore essential to the survival of Eastern Bristlebirds. The major decline in wild bristlebird numbers since the 1980s can be mostly attributed to the cessation of regular planned fires plus one extensive, hot wildfire.

The owners of the Land for Wildlife property with the Eastern Bristlebirds are cattle graziers who use fire as part of their land management strategy. They burn sections of their property every few years to encourage palatable grasses for their cattle and to minimise the risk of wildfire. Healthy Land and Water has longsupported the owners with weed control and the construction of fire breaks to assist with fire management enabling them to burn downslope.

When preparing a site for a planned burn, Lantana and Crofton Weed are first sprayed and killed to help create enough fuel for the fire to be carried as well as reducing the total number of weeds. Fires are generally lit along one front giving bristlebirds escape routes. Ideally, bristlebird habitat is burnt about every 3-6 years depending on rainfall. Planned burns are designed to create a mosaic patchwork of burnt and unburnt areas. Close-by gullies and rainforests are key refugia for bristlebirds and all known bristlebird territories adjoin rainforests or dense wet sclerophyll forest, which are not burnt.

The Eastern Bristlebird Recovery Plan guides on-ground work for wild populations as well as recovery activities for the captive population. Habitat management activities occur across private and public land (National Parks) in NSW and Queensland with regular cross-border collaboration. For example, Penny is owned and managed by the NSW Office of Environment and Heritage but also does survey work in Queensland. Eighteen private landholders are engaged with the Eastern Bristlebird Recovery Program, with appropriate fire management plans developed and being implemented. Similarly over the past 30 years, fire management within National Parks has been modified to restore and maintain bristlebird habitat.

Hopefully in the decades to come, the wild population of Eastern Bristlebirds will increase. New populations could be re-introduced to appropriately managed areas using captive-bred birds. As we know with the Californian Condor, successful recovery programs do work, but they can be expensive. If you are in a position to donate to threatened species recovery, then I encourage you to consider investing in the Eastern Bristlebird Recovery Program by supporting Currumbin Wildlife Sanctuary.

Article by Deborah Metters (Healthy Land & Water) with thanks to David Charley (WildSearch Environmental

Services), Liz Gould (Healthy Land & Water) and Lynn Baker (NSW Office of Environment and Heritage)